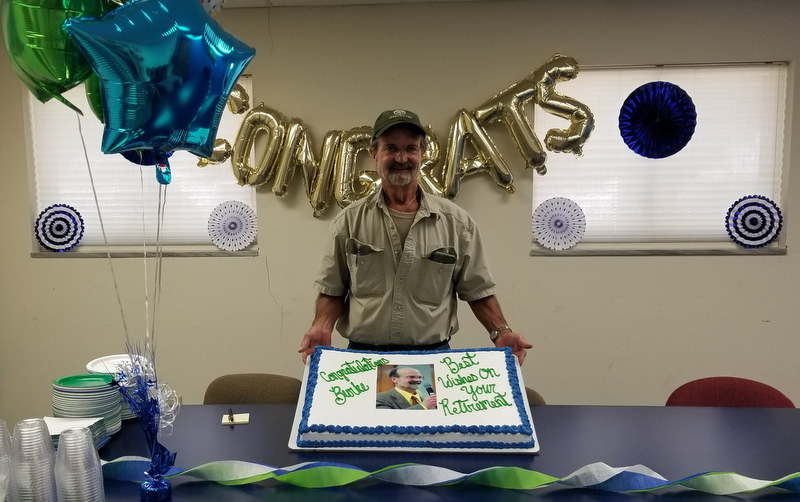

Community members visited Marion County Soil & Water Conservation District Wednesday to acknowledge Burke Davies’ four decades of service in the field of conservation agriculture.

Burke has served as resource coordinator for the district in Salem since August 1987, and his agriculture life has included everything from walking beans, reclaiming mines, spending days in the snow and rain mapping soils, a tussle with barbed wire and 37 years assisting producers secure grants to support conservation agriculture.

Growing up, his mother Janetha Hawkins came from a farm family, and Burke had relatives with small fields in south Marion County. The family did not have big farm operations, but their small farms featured livestock, chickens and some row crops. His father, William, would take him hunting and fishing and get to know the Southern Illinois region, and instilled in his a love for the outdoors. Burke walked beans in grade school, and bailed hay and straw and was a dishwasher at the Hi De Ho Hotel & Restaurant to make money in high school at Carlyle.

Burke received an associate degree in science from Kaskaskia College, then to Southern Illinois University-Carbondale for undergraduate studies in general agriculture. He was helping in the labs with soil testing, and one of his professors asked if he would be interested in continuing on as a graduate student working on strip mine reclamation. His research was on alternative methods in lieu of topsoil replacement on strip mine sites. He did this for 2 1/2 years, using a Texas Instruments TI-35 calculator. For fun he and his fellow graduate students would play a trick, and flip one of a stack of punch cards so the computer would run in an endless loop, spitting out a stack of paper off the dot-matrix printer.

Burke had memorable experience going to Washington DC to present a paper on his reclamation work. While there he met a “Beltline Bandit,” a retired military contractor who told him the subway stations of the Metro were overbuilt to serve as bomb shelters, and told him where locals would go to get a cheap hamburger. Visiting the capitol on a graduate student salary was a stretch, so knowing he could get a budget meal at a drug store counter, which were always packed with locals, was key.

After graduate school he worked four years in the field, creating soil maps. “We didn’t have LIDAR like we do now,” he said. Burke would head out each morning, sharing a United States Department of Agriculture car with another another county soil scientists. He’d get dropped off by 8am, eat lunch in the field, and was picked up at the end of the day. Every week they would switch drivers, alternating who got to keep the car with him.

“We enjoyed being out there,” Burke said. “We’d be in the field, in the rain and snow for hours, waiting for your ride to come pick you up.”

Burke said in a sense they were uninvited guests. Some landowners didn’t get or read the letter saying someone was coming to map their soil. So he would knock on doors to let landowners know what he was up to, enabling him to meet producers and get to know people. The only negative experience he had was with barbed wire. A pole broke while he was crossing a fence, and Burke had to hobble around and finish his work until the car came to pick him up. He later had to have knee surgery.

After four years of knocking on doors and hopping fences, National Resources Conservation Service District Coordinator Jim Wallis asked if Burke would consider a job working with Marion County Soil & Water Conservation District. Since that point in 1987 he’s worked for Marion SWCD as a resource conservationist. Early in his career he worked Saturdays and Sundays mapping soils in adjacent counties for extra money, but mostly his work as resource conservationist has been all-encompassing. Over the years, depending on the budget and who else was working in the office, he was the person managing the equipment rental, working out cooperative agreement, and handling fish and tree sales.

Like the feather in Forrest Gump, Burke said “I just wound up in the right place.”

With his origin story identifying soils, Burke says the Conservation Reserve Program has made the biggest impact. He would just know by the slope of the land, and the soil type, that CRP was the best way to go. Burke could go out in the field with the farmer and illustrate the loss of organic material.

And even today with all the data available online, Davis prefers being grounded on the land. He said the job used to be 80 percent in the field, and 20 percent in the office. Now with technology and with the data available online, those percentages have flipped. He said “I still like sticking a probe in the ground and identifying the soil,” then compare with web soils survey data on the compuer

And Burke says farmers now have more access to information. They see articles and social media posts on soil health, making them more receptive to giving new ideas a try. “Sometimes they’d see a neighbor try something new and think ‘that guy’s crazy,’” Burke said. “But then they’d see the results, and that would change some of the older farmers’ minds.”

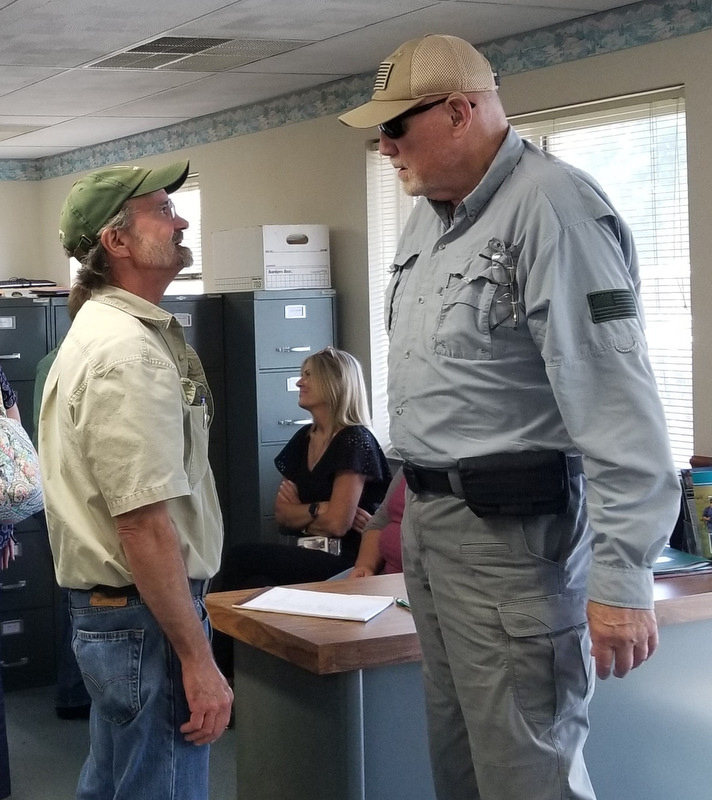

During his time working for Marion County SWCD, Burke has worked with three generations of farmers. When you’ve helped someone’s grandpa make his operation better, you have intergenerational trust with the grandson. Even beyond work, Burke would sit around and chat with farmers, fish their ponds, go mushroom hunting, or just visit with them. “I usually get more sweet corn than I can handle, it’s on my porch when I get home,” Burke said.

As for Zach Lowery, the next person fill the shoes as resource conservationist, Burke hopes Zach enjoys the work as much as he has, and that Zach gets to meet all the farmers and non-farm groups out there in Marion County. Although Burke’s annual contract has expired, he continues to accept one-month extensions as Marion County SWCD struggled to find a replacement. Burke can finally step down in October. “I’m now retired – I don’t want them to call me back,” he joked.

So what’s next? Burke has been on the Centralia Balloon Fest steering committee for 20-plus years. And he works with Mission Centralia to build ramps for folks who need help accessing their home. The group surpassed the 100-ramp mark this year. And while Burke said he doesn’t have the carpentry skills to build a house himself, he can do a ramp, a birdhouse and maybe a doghouse. He will have more time with his wife Kimie, and their daughter Karly lives near them in Centralia.

And besides hunting, fishing, or venturing out to find some chicken of the woods, or staying home to check off his list of things to do, Burke said there’s work to do in his garden. In addition to beans, tomatoes and peppers, he’s also growing awareness of no-till practices. Burke’s been gardening for 10 years now without tillage, plus having something growing year-round, and he says his soil has great aggregation, color and organic content. After a rain he has no ponding or puddling, and his crops have been growing well.

“My neighbors don’t know why I don’t own a Rototiller. No-till and cover crops are something to believe in. It really does work.”

Photos courtesy of Judy Beyers and Patricia Lund.

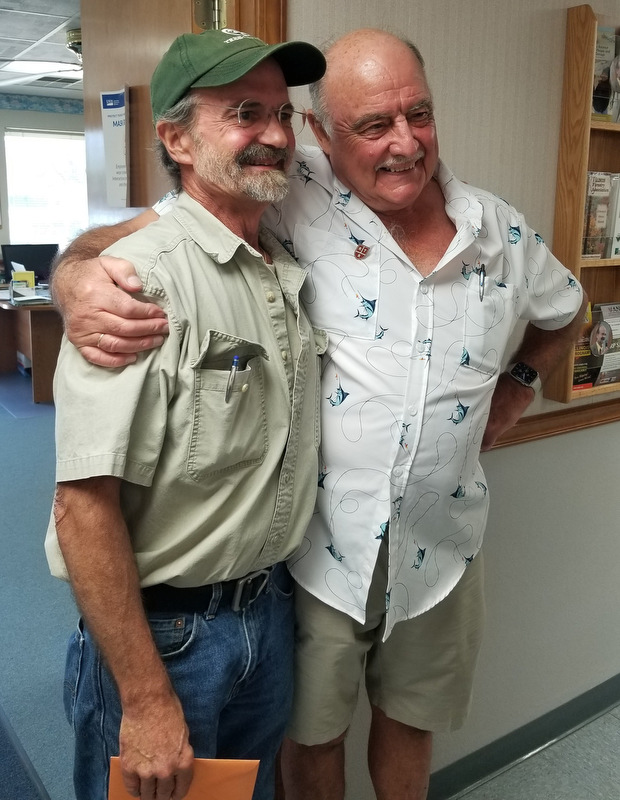

Retiring RC Burke Davies with “long-time lunch/ work buddies” Tom and Judy Beyers and Harold Hunzicker.

Retiring RC Burke Davies with wife Kimie and daughter Karly and her boyfriend Charlie Hopkins, and former SWCD-ACs Dorthy Smaller and Debbie Holsapple.